Kesennuma Master Plan

Reconstruction Plan, Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan

Design Team frontofficetokyo

Felicity Barbur, Joris Berkhout, Laura Dianu, Will Galloway, Ana Ilic, Koen Klinkers, Daniel Lauand, Jessica Leung

Research Group at Keio University

Professor Wanglin Yan, Professor Hikaru Kobayashi, Professor Tomoyuki Furutani, Kazunori Tanji, Project Assistant Professor Will Galloway, Akihiro Oba, Tomoki Kobayashi, Tomoyuki Ikeshita, Kentaro Nakada, Takahiro Kanamori, Shione Murasugi

Reconstruction in Kesennuma cannot be limited to a simple re-building of the homes and businesses that were lost.

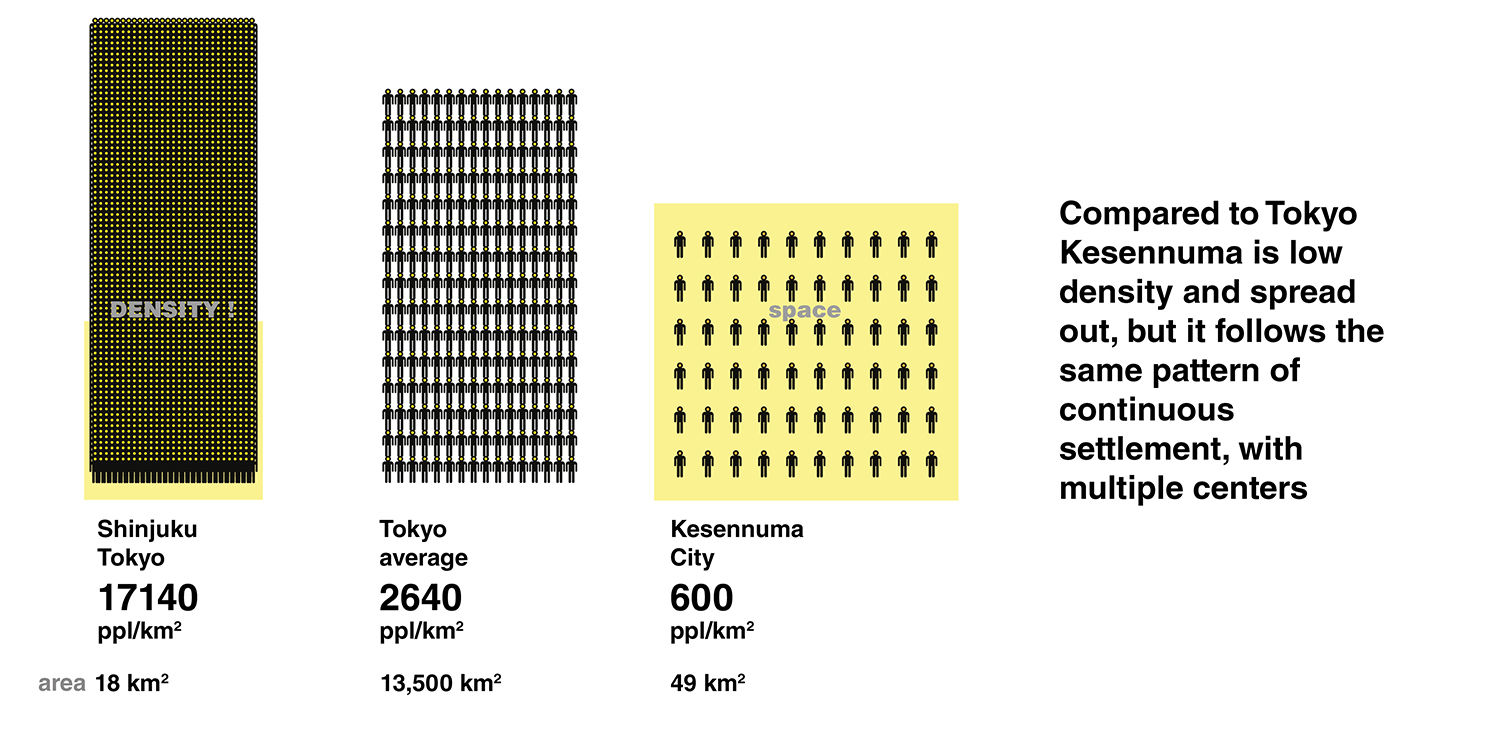

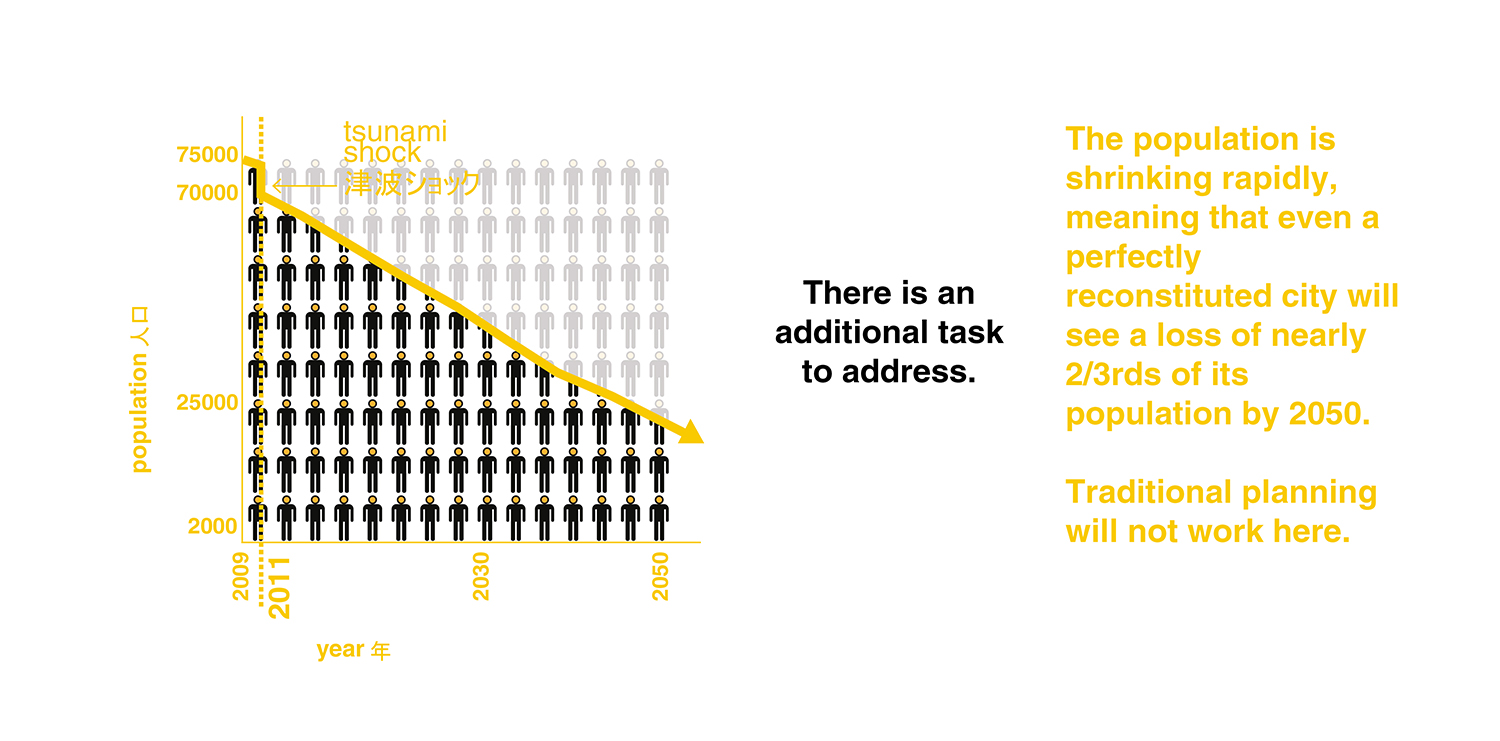

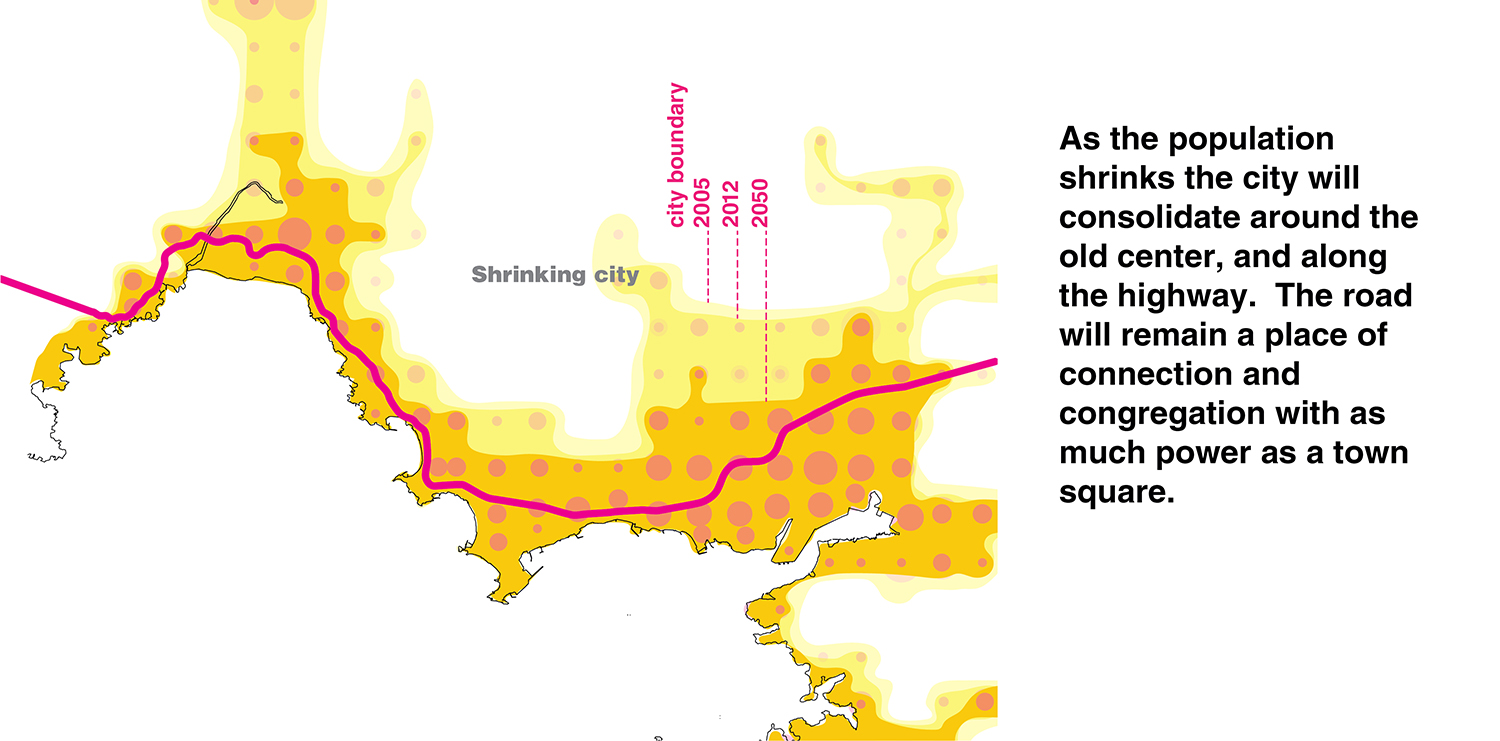

The demographic future of the city will almost certainly be defined in by a shrinking, aging population. If we are honest about how to rebuild for that future, it is essential that those realities are accommodated without the loss of community, a pillar of resilient society. Traditional urban forms will not be sufficient.

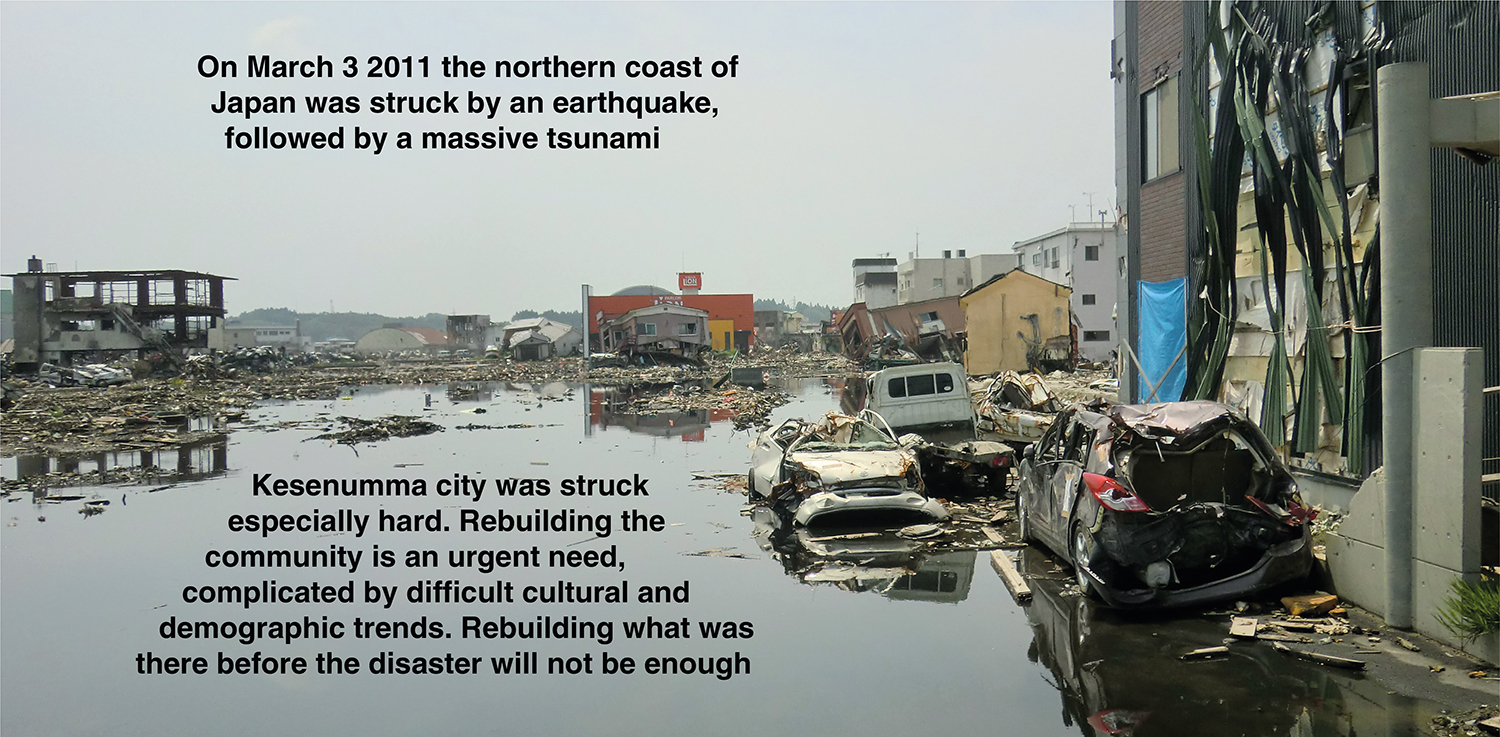

The devastation caused by the earthquakes and tsunami that hit Tohoku on March 11, 2011 underline the need to build back better, and to create a resilient community typology. This mean new social forms, and additionally must include new physical landscapes that are both easy to access and locally sustainable in terms of energy, commerce, and social cohesion.

In this case a compact city in 2016 will be a ghost town by 2040. The design must be adaptable enough that radical de-population (nearly 50%) will not hurt the community.

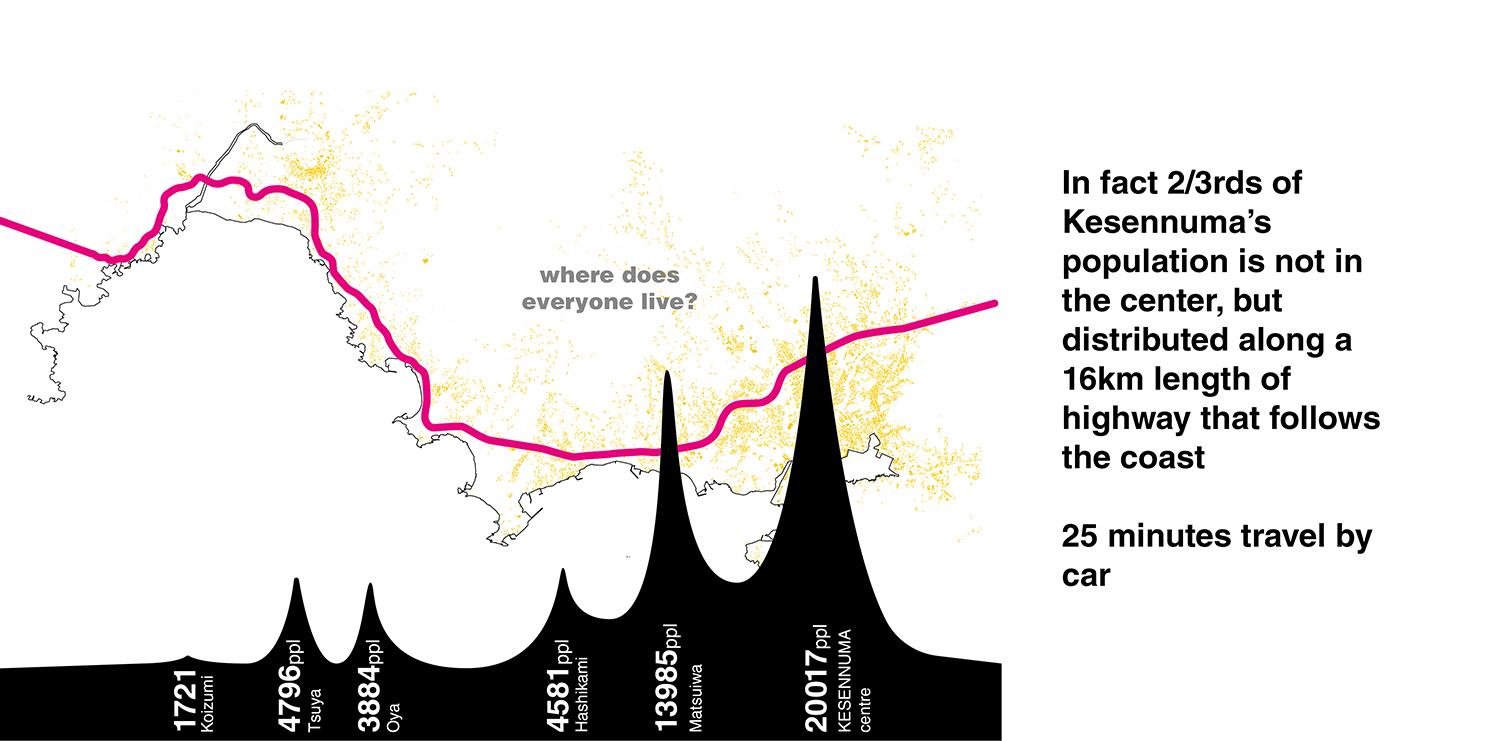

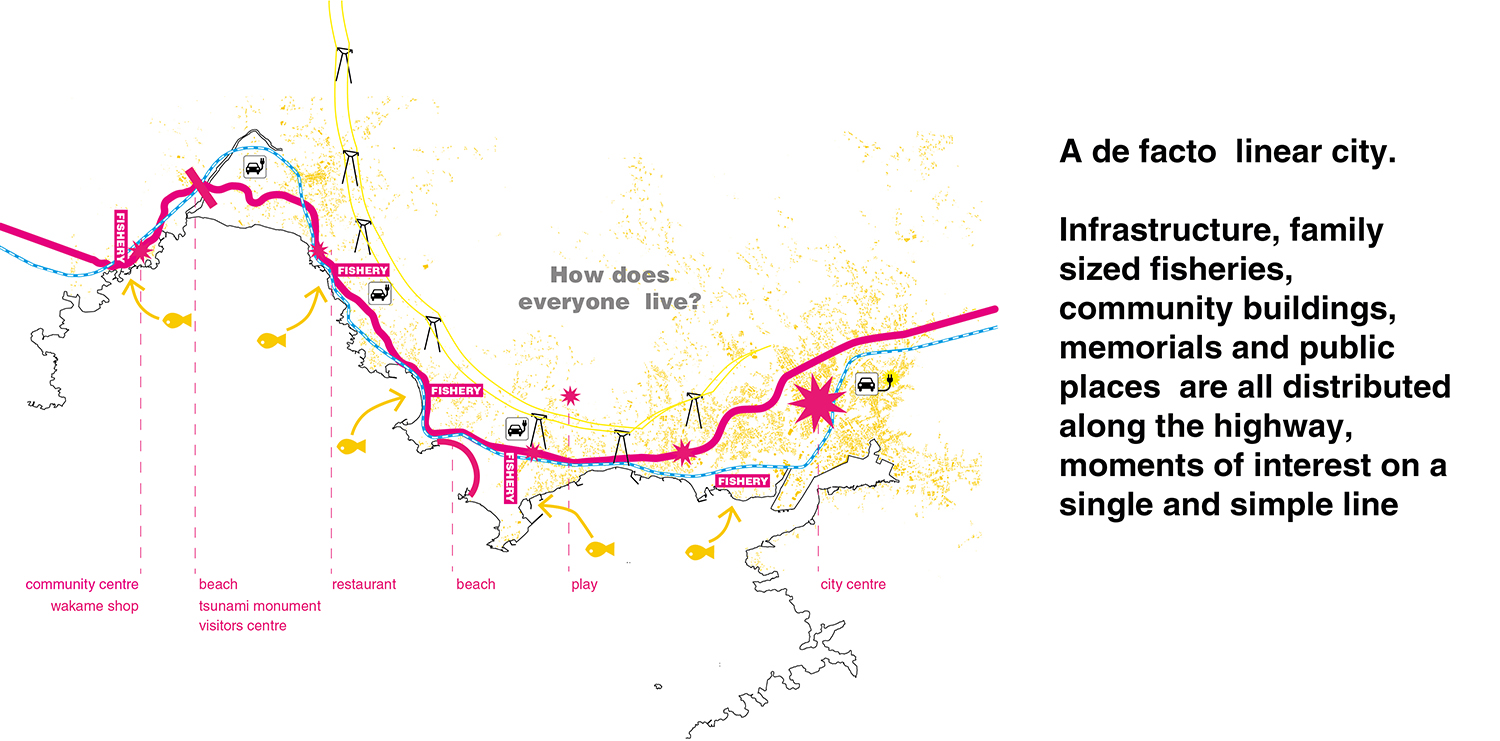

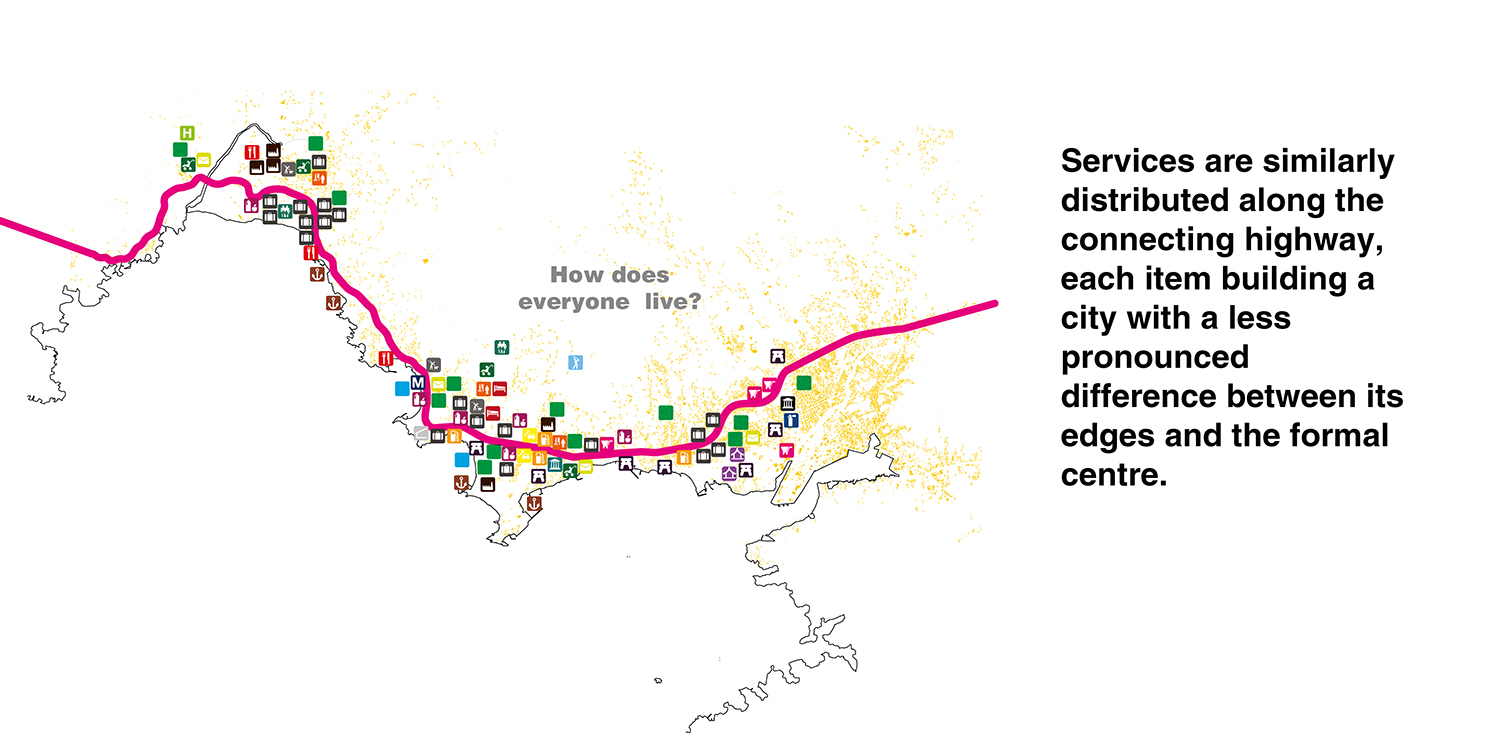

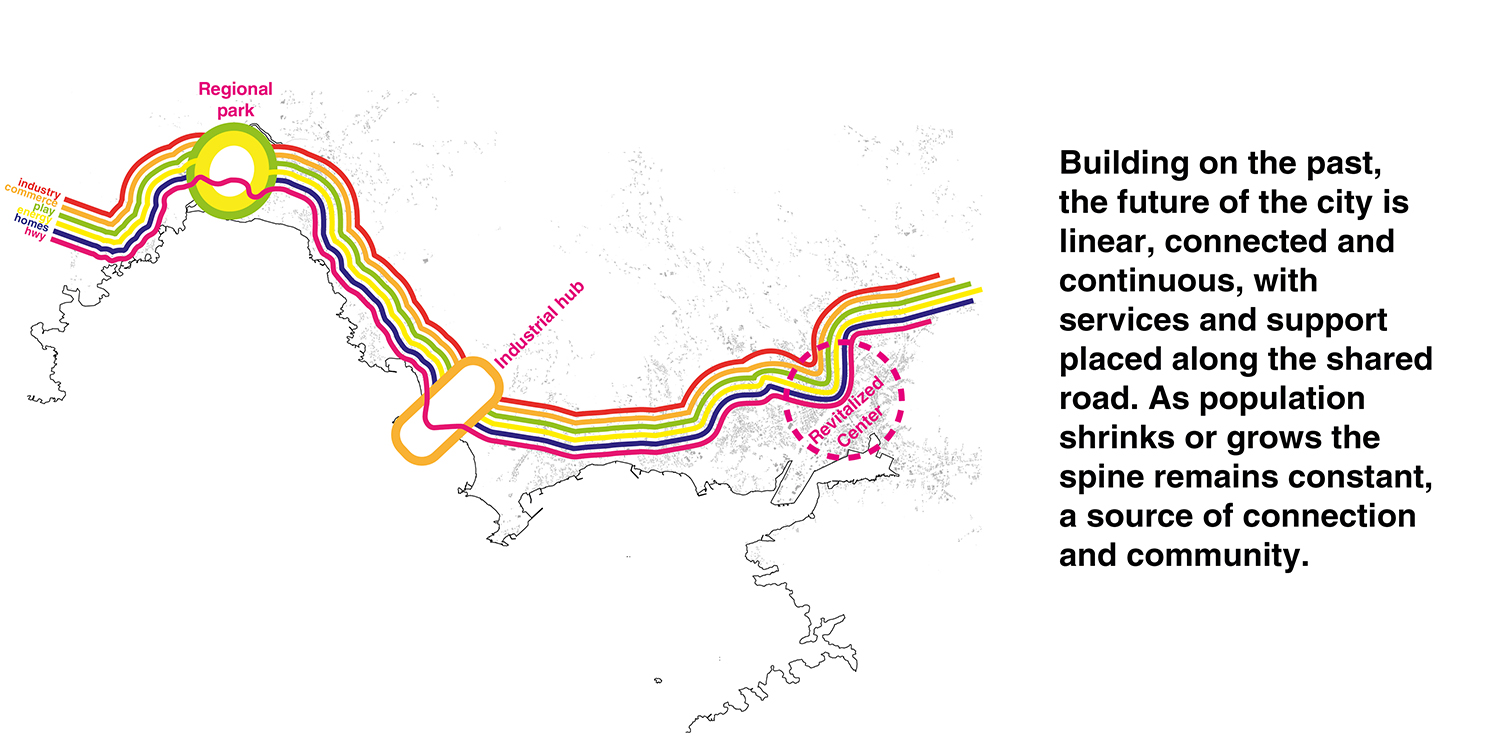

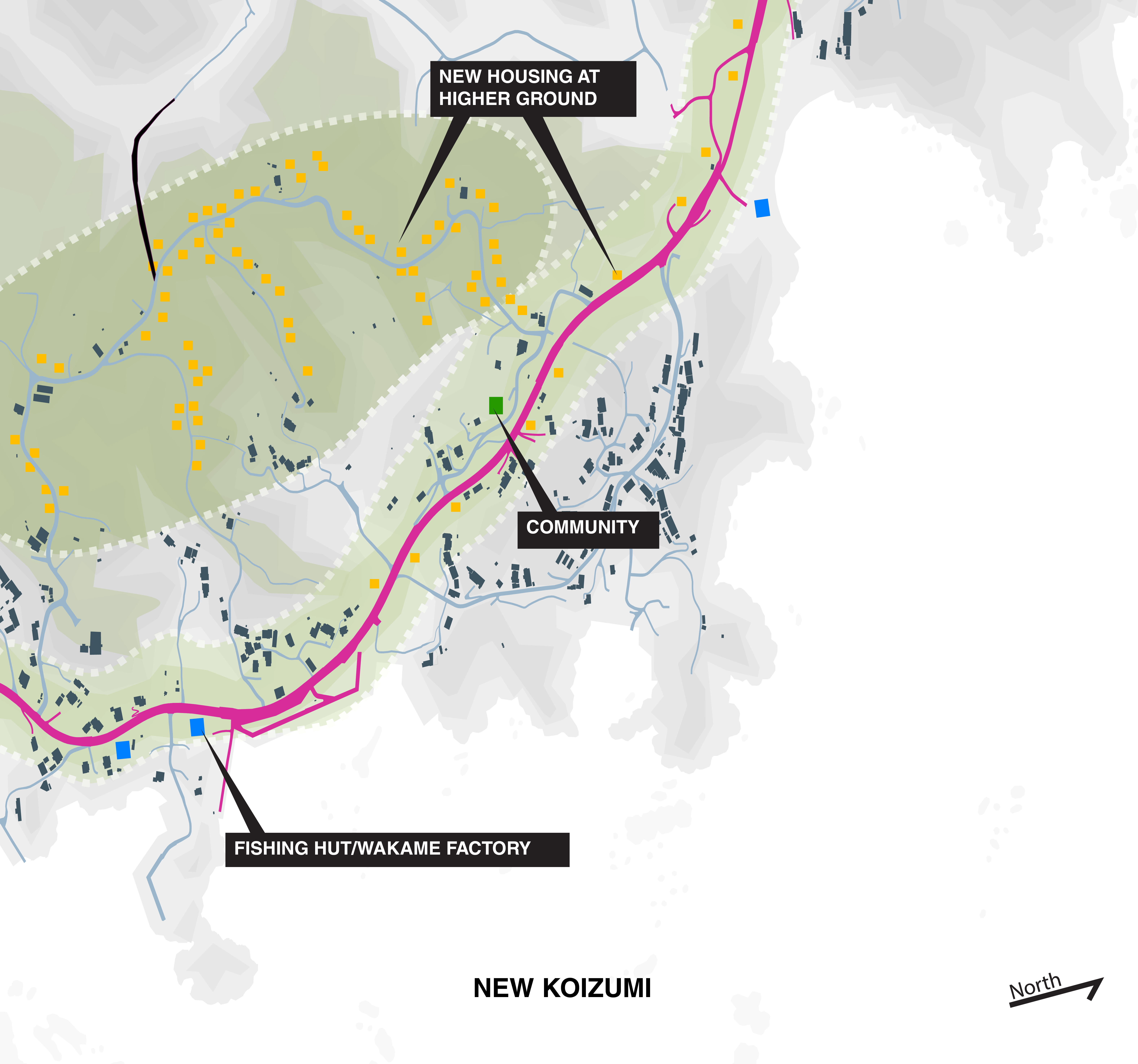

Energy, tourism, education, health, commerce, and community are treated as a network. We propose to build back an interconnected group of functions that intertwine like a thread through the region, with important communal activities taking place both in the village setting but also on the main roads that connect each group of residents together. Infrastructure is a long-term commitment and attractor. While houses will become vacant, the roads, the businesses, the services that make community possible, can all be maintained along a single road.

Important community functions are located on the connections between homes. The sense of community does not rely on density but instead is embedded in access. In this way, the future can be accommodated, whether population shrinks or expands, grows old or is filled by youthful immigrants, or an entirely different mix emerges. Technology can also be absorbed and energy systems added and modified as it becomes available. The aim is healthy communities, but the approach is flexible rather than prescriptive.

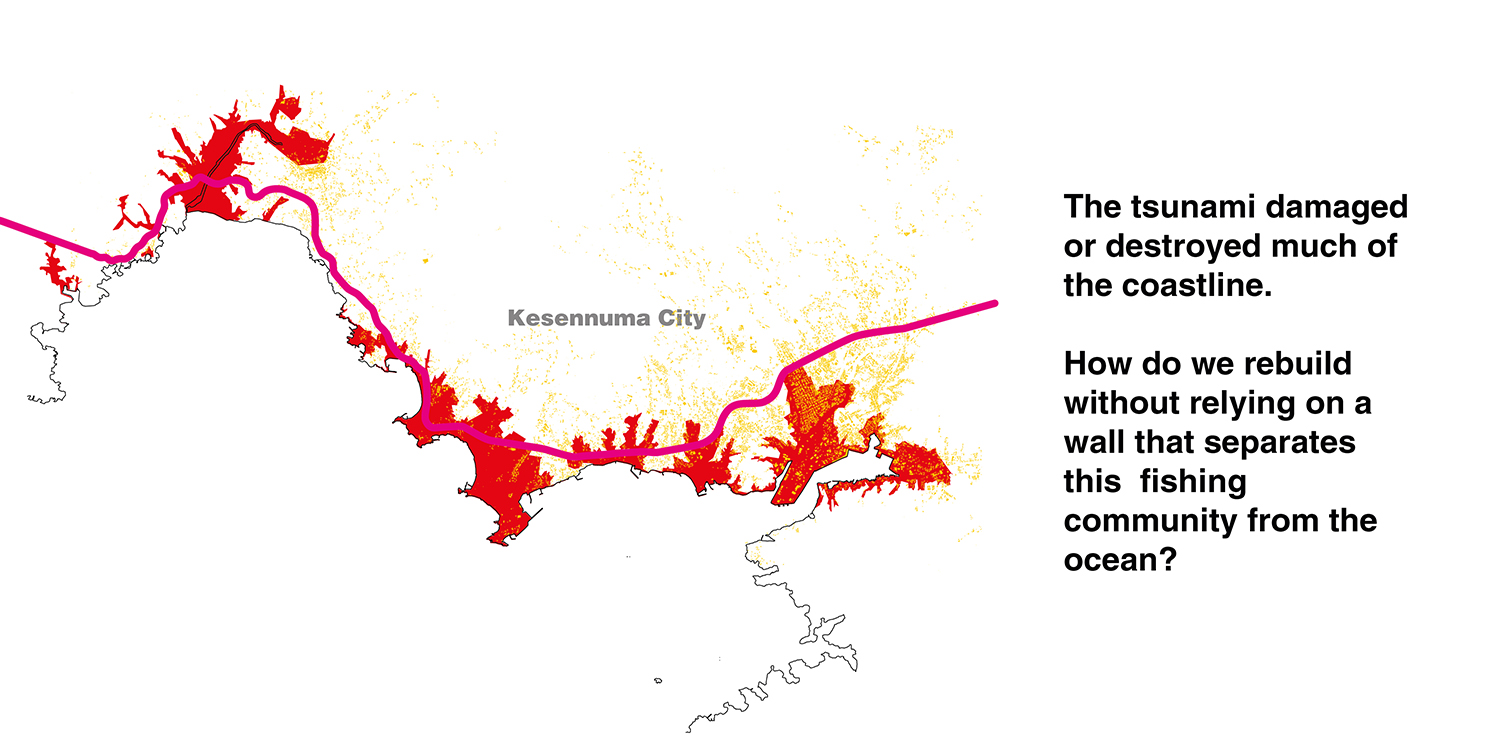

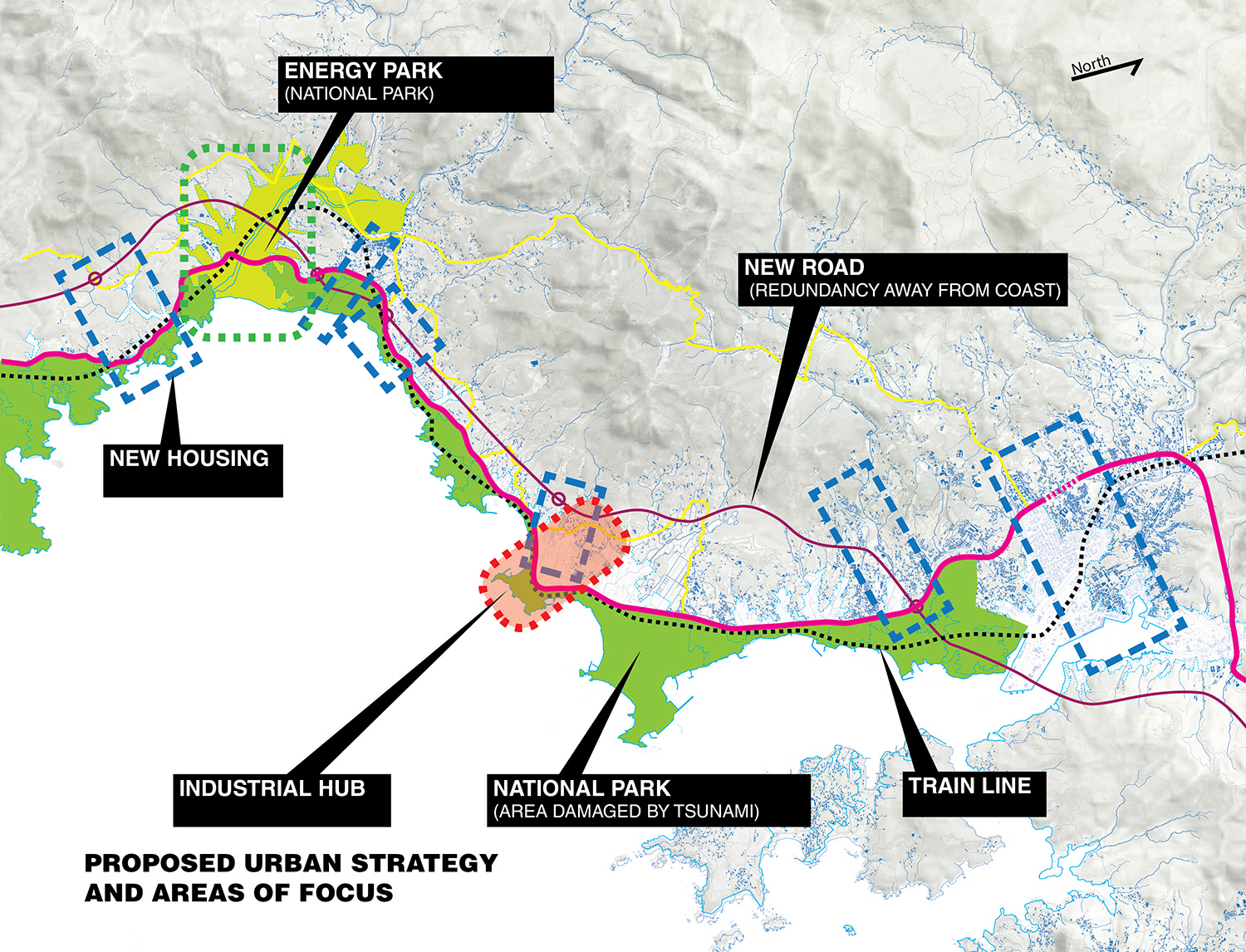

In practice this means we work at the large scale and the small at the same time. The coastline is not safe to build homes on, and a sea wall will disconnect the fishing communities that live in the area. The way forward is to create a national park on the coast, intended for play, leisure and outdoor work, while homes, larger industry and commerce are set higher up the landscape, beyond the connecting road that links the residents of Kesennuma to each other. The road acts as a simple marker of safety, built into a rich and protecting landscape.

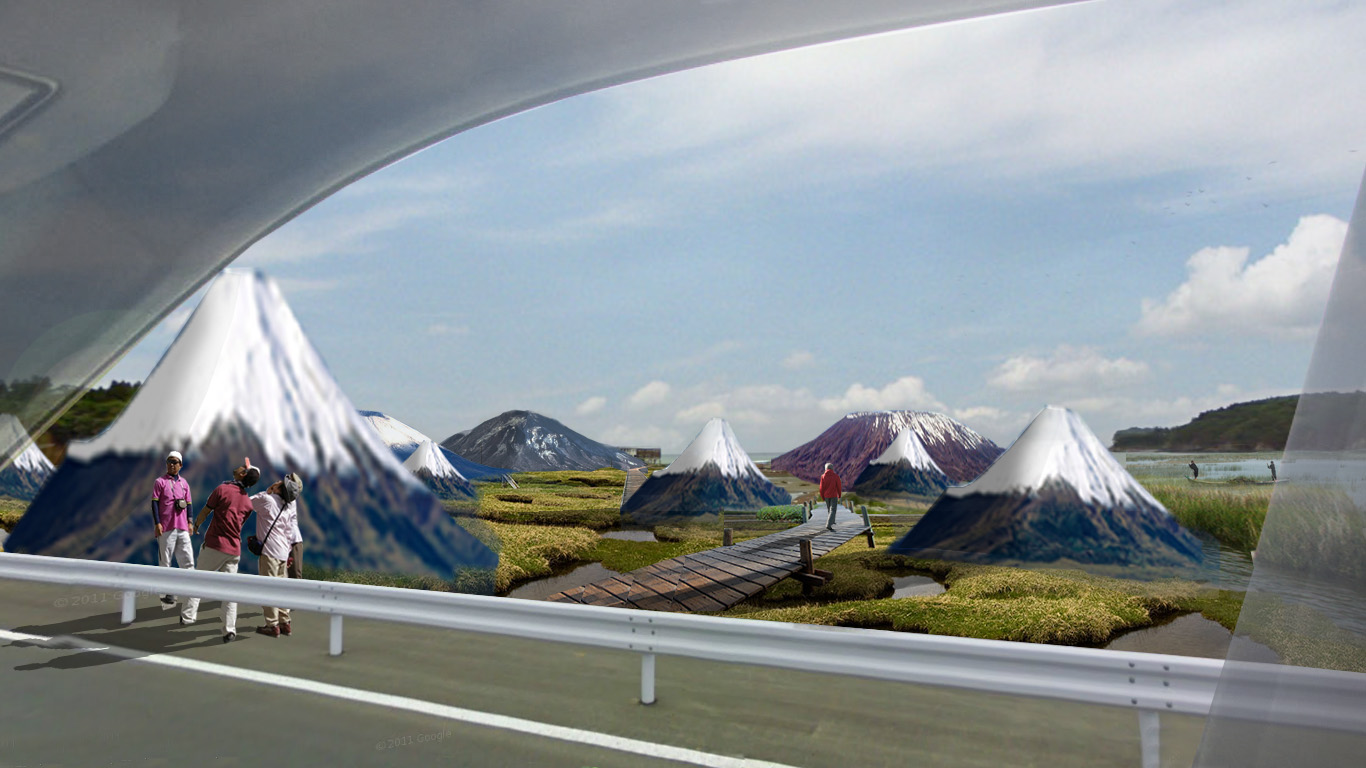

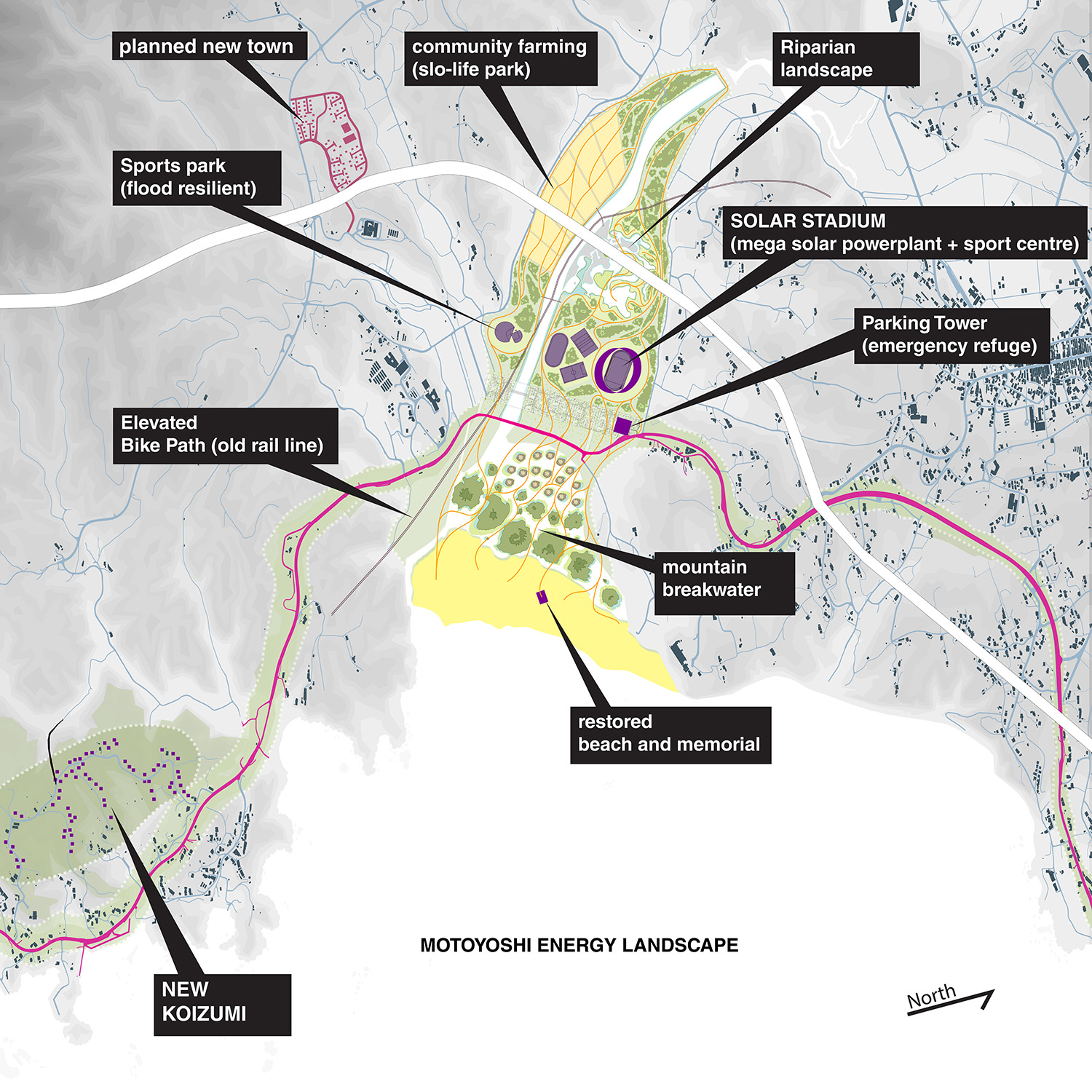

The large river valley is made into a mega-scale solar energy power plant and park, serving the local communities as well as visitors. Here the services do double duty, so a parking tower is a refuge, the solar power plant is the canopy of a simple stadium, the landscape is a breakwater and a barrier where needed. Resilience in this case is about being ready for extreme events while also creating a place of comfort and enjoyment.

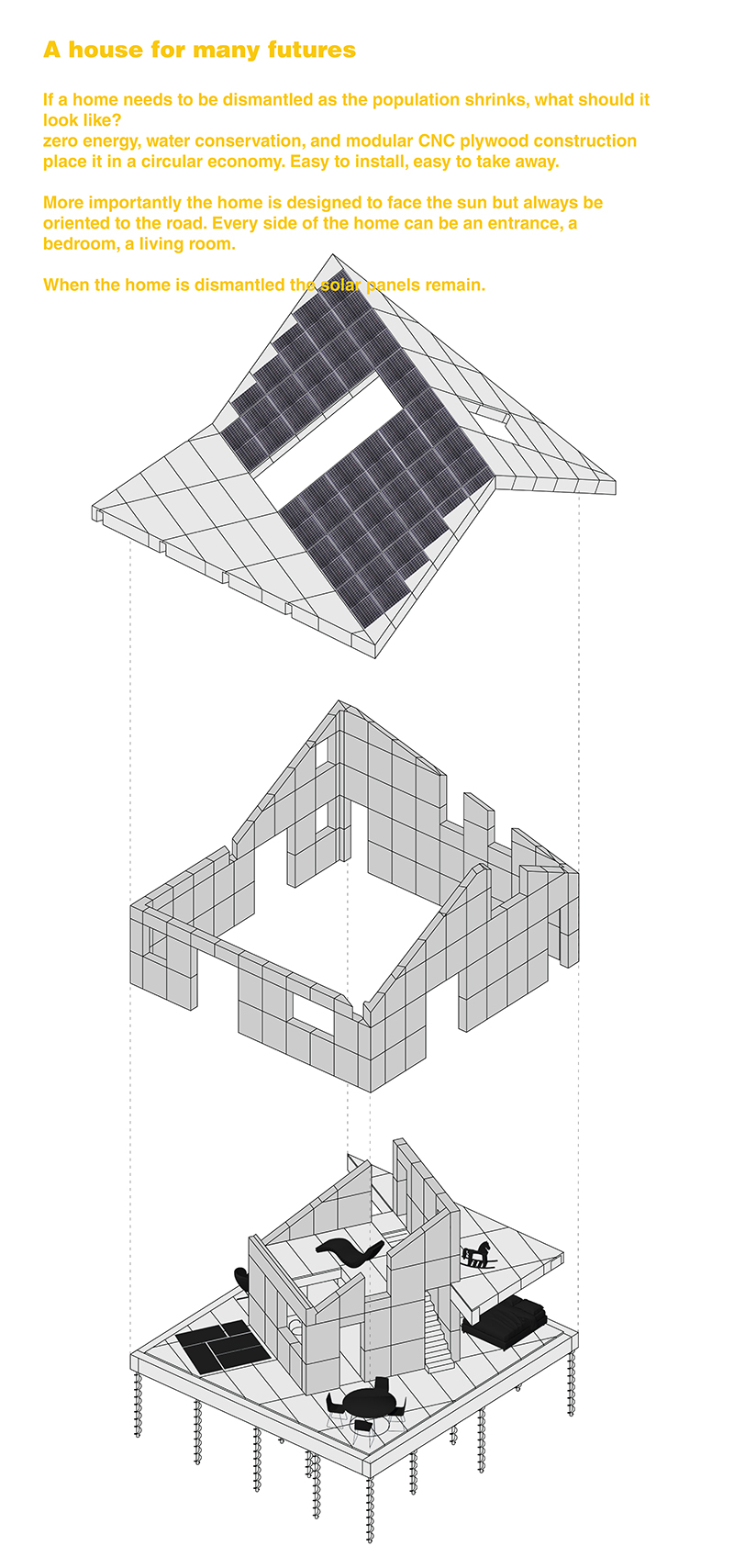

Fitting into the new landscape along the road are a series of modular homes, fishing huts, community centres, all made for easy construction and easy removal as needs change into the future. These small scale additions to the landscape work together to create a network of communal energy production, water storage and place. Homes are modular and repetitive but take on a different character as they orient to the sun and road. Over time they will change their appearance and become singular, they will be romved, leaving the solar array behind, and they will change function, from homes to shops, to small hostels. Without knowing the future the aim is to at least be open to as much change as possible.